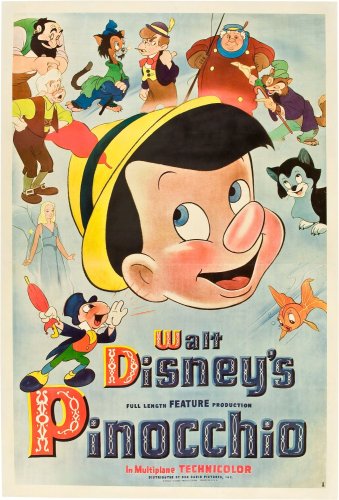

“Pinocchio” is a one-of-kind gem in the Disney Canon. Disney has always adapted a lot of grim fairy tales, novels and folklore – distilling some of the more gruesome elements into cheerier, contemporary films that still retain the themes and ideas of the source material – and it does so rather well. “Pinocchio” is quite rightly remembered as one of the few Disney films that are genuinely, unrelentingly frightening. Because, here’s the thing about Disney. The studio is extraordinarily good at invoking mood whiplash when it does so deliberately. “Mulan” followed up a hearty road trip song with the intrepid heroes making a very morbid and bloody discovery out of nowhere, and “Robin Hood” was a lively, lighthearted romp that got very dark in it’s last act.

Likewise, “Pinocchio” starts off as a cozy, whimsical, wholesome story centered around a small clan, that’s about love, family and your dreams coming true, and then it gradually turns into a ghost train ride or a G-rated horror movie – starting from the moment Pinocchio, the wooden boy, innocently lights his own hand on fire. “Pinocchio” benefits a lot from having excellent pacing. It’s slow-burning but never boring, giving it’s darker moments time to simmer and contrasting them with the innocence and ignorance of it’s lead. Letting dread build and sinisterness spill off the screen, taunting the audience with the knowledge that Pinocchio is in too deep, before it finally strikes forward savagely, like when Stromboli finally shows his true colors to the boy. The strongest and most iconic example of this is the Pleasure Island sequence.

At Pleasure Island, Pinocchio and dozens of other little boys are ‘generously’ allowed to indulge in every vice they can imagine by the Coachman. They smoke, drink, fight, wreck everything they get their hands on, and generally behave like animals, and Pinocchio, despite knowing better, joins in with encouragement from his pal Lampwick. The following night, when the park’s gone far too empty, Jiminy Cricket tries to talk some sense into the boys but just winds up being pushed around and humiliated by Lampwick – the audience is reminded that the ugly side of human nature isn’t just exclusive to adults. Children can be pretty awful as well.

Jiminy does manage to uncover the truth of Pleasure Island though. The park’s proprietor turns it’s inhabitants into literal animals, stealing their voices so they can never speak another word and selling them into slavery and hard labor for the rest of their lives. He’s in the market for slaves. Pinocchio and the audience watch Lampwick undergo a werewolf-like transformation, losing his mind and his humanity screeching – metaphorically dying – before Pinocchio and Jiminy are forced to flee the island and abandon everyone there to die, lest they be turned next. And this is the final fate of the Pleasure Island boys. No one ever comes back for them and as far as we know, they’re never rescued. It’s one of the most brutal things Disney has ever done, one of the most honest (if you stray too far from home and ignore all your instincts, you could land yourself in some trouble you’ll never get out of) and by far, one of the most memorable.

However, “Pinocchio” does have its share of flaws. While the first two acts segue into each other quite nicely, a surprisingly large amount of plot-holes and unanswered questions surface when Pinocchio mounts a rescue mission to save his dad from Monstro in the last act. For example, why did Gepetto decide to look for Pinocchio out at sea of all places? Where did he get a boat from? Did he always have a boat? Gepetto states he hasn’t caught any fish in days and is on the verge of starving, but the film makes it clear Pinocchio and Jiminy were only away from home for two days tops (they escape from Stromboli, hop on a midnight barge to Pleasure Island, spend a day there and rush home) and Gepetto almost certainly set out looking for them on the second day, so when did he find time to starve?

Why can Pinocchio and Jiminy Cricket breathe underwater? (Pinocchio, I can understand, he doesn’t have lungs). Presumably it’s because of cartoon physics, but if that’s the case then why does Pinocchio later die by drowning? (At first I thought it was because he’d been fatally throttled by Monstro, but upon rewatch it was death by drowning). The whale chase sequence is one of the most thrilling and well-animated climaxes in the Disney canon, but the circumstances surrounding it are more than a bit contrived. Along with the movie operating on fairy tale logic, the fact that Carlo Collodi’s “Pinocchio” was an episodic novel and Disney had trouble tying the story together for a feature film probably explains the cracks in the film starting to show in the last twenty minutes. It’s a mark against the movie, but it’s far from a deal breaker.

One of the most notable departures from the source material is Pinocchio’s characterization. While Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio was a cold, cruel and sociopathic creature, the titular character of Disney’s second film is a lovable, enthusiastic, naive child who tries to impress his friends and his father, and maneuver his way through a new, unfamiliar world – often stumbling along the way. Due to “Pinocchio” as a movie having a surprisingly great understanding of children and containing a lot of childhood fears (some adult fears as well), the living marionette’s character arc throughout the film winds up encapsulating a lot of the experience of being a young kid. Like looking up to your parents, being tempted to blow off school, ignoring the advice of grown-ups, getting in way over your head, lying to avoid disappointing others, being afraid of losing your family, gaining friends who are a bad influence on you and learning to value the really good ones you’ve got.

Despite his frustrating failures, time and again, to stick to his convictions, the audience is always reminded that Pinocchio is a good kid, and during the last act of the film he shows a plucky, heroic and determined side to him. He ultimately proves himself worthy of being a real boy by venturing into extreme peril, using everything he’s learned throughout his journey to his advantage, and doing everything in his power to make up for his mistakes and save his father’s life. Mind you, a lot of this movie’s plot could have been avoided if Gepetto had walked Pinocchio to school himself on the boy’s first day existing, but where would be the fun in that?

Pinocchio is guided along the way by vagabond-turned-conscience, Jiminy Cricket; his wry, sassy, and supportive sidekick who more than earned the expanded role he was given in this film. Jiminy starts out a homeless fellow and a drifter, who by chance finds himself unexpectedly drawn into the movie’s events and tasked with being one of Pinocchio’s caretakers. Jiminy is an older fellow with a good head on his shoulders, and is more than a bit quirky. He sometimes feels like a cross between a father-figure and a minister, gently admonishing Pinocchio for his failings and warning him about the dangers of earthly temptations (for modern viewers, the lesson about staying on the straight and narrow can sometimes feel a bit heavy-handed).

Despite being the voice of reason and morality in “Pinocchio”, Jiminy is far from perfect and has his own flaws and shortcomings as a person he needs to navigate through. He abandons Pinocchio twice, once out of self-doubt and once out of temper, and he’s also kind of vain at the start: desiring a badge from the Blue Fairy and deciding not to seek help from Gepetto, which could have saved them all a lot of trouble, in favor of not being a ‘snitch’. Still, Jiminy is as true a friend as you can get (especially for a very recent one), following Pinocchio through all sorts of nightmarish scenarios like Pleasure Island, all the way to the bottom of the sea. Amusingly enough, Jiminy also has quite an eye for the ladies, particularly human women, and sometimes tries to put the moves on them, despite, y’know, being a cricket.

Being the first of several single fathers in the Disney canon, the kindly, absent-minded woodcarver and toymaker Gepetto brings a strong, paternal warmth to the film. Gepetto lives alone with only his pets and his inventions for company, and he wishes for a son that he’s far too old to have naturally these days. He gets his wish, as a gift from the Blue Fairy, and he treats his magical, miracle boy with plenty of love and care. Once we get into the second act, Gepetto grounds an otherwise fantastical movie with the comfort and familiarity of home, just waiting to be found again by our lost hero. Despite the sentimental old guy not appearing much outside the first act, he ends up being one of the more memorable and loving father figures from the House of Mouse.

Gepetto is accompanied by his faithful pet, the stroppy, long-suffering kitten Figaro, who acts as Gepetto’s second-in-command and is quite the scene-stealer with his short-tempered antics. It’s easy to see why the mischievous but devoted kitten was later made a recurring character in the mainstream Mickey Mouse shorts, as Minnie Mouse’s cat. The enigmatic but benevolent Blue Fairy, who animates Pinocchio, only appears in person twice in the film, but her magical, motherly influence reaches throughout. Curiously enough, she looks like Snow White all grown up (and apparently they shared the same animator). She’s the closest thing Pinocchio has to a mother figure in the film, and her standout scene has to be the cute but sad sequence where she disciplines Pinocchio for lying and teaches him a lasting lesson about the importance of honesty.

Instead of a single, overarching villain, “Pinocchio” has a string of increasingly dangerous antagonists, many of whom have a certain kind of charm to them but prey upon Pinocchio’s lack of worldly experience in a manner most disturbing. The first in the line-up are Honest and John and Gideon, two illiterate, manipulative, small-time conmen. Honest John tends to do all the talking (literally, since his partner is mute the entire movie), while Gideon does the grunt work. The two of them pull Pinocchio off the street on the way to school and sweet-talk him with promise of fame and fortune. They propose he ditch school and try to become an actor, and against his better judgment and Jiminy’s warnings, Pinocchio follows them.

Of course, Honest John and Gideon have no morals, principles or loyalty, so they quickly sell Pinocchio out for a profit (a talking wooden boy is a rare, valuable commodity). Which introduces us to our second antagonist, a greedy, bombastic, child-abusing showman named Stromboli. Stromboli is a very ruthless Italian puppet-master with a short temper, but he sees the potential in Pinocchio as well, so he gives off a genial vibe for a while and pretends to be Pinocchio’s friend, right up until the moment Pinocchio suggests going home and telling his father about their arrangement. At which point, Stromboli traps him and imprisons him, planning to exploit him as a singing dancer for however long he’s profitable, after which he’ll chop him up as firewood. Well, that’s unsettling. It’s only with the help of magic that Pinocchio gets out of that kidnapping predicament, and what’s worst, it’s the first and only freebie he’ll receive in the film.

The next antagonist is easily the most redeemable and more of an anti-villain than anything: another boy Pinocchio’s age named Lampwick. Lampwick is a crass local bully and ruffian, a wild child who lives a hedonistic lifestyle without rules or adult supervision. However, Lampwick does become a genuine friend to Pinocchio and takes him under his wing, even if he’s not a good influence on him. The tragic thing about Lampwick is that he could have easily learned the error of his ways and grown from them, but unlike Pinocchio he never gets the chance. He’s taken out of the picture indefinitely by the Coachman. The Coachman is a dastardly, amoral, satanic slave-driver, who probably has the blackest heart and most evil intentions of all the villains. His power is beyond our heroes, and the only thing they can do is run from him ultimately. The last villain is the most fearsome one: a colossal, ravenous, infamous sperm whale named Monstro who has a terrible temper and can easily crush our protagonists like they’re nothing, as he tries to do during the climax.

While poor Lampwick is sentenced to a fate worse than death when his lifestyle choices catch up to him, about half of these guys never have their storylines wrapped-up neatly or receive any sort of comeuppance for their evil. Monstro beams himself to death on some rocks and Honest John receives some preemptive, well-deserved abuse from Gideon with a mallet, but guys like Stromboli and the Coachman simply carry on with their lives after their brief encounters with Pinocchio, free to cause even more damage. In some ways, the lack of closure these figures receive makes them even more real though, and ties into some of the more cynical acknowledgements the movie makes. These characters do have lives beyond being villains in a little wooden boy’s story, and in real life, not every villain gets their due. Not every one can. It’s just one more reason why you’ll want to be careful who you put your trust into.

If there’s one thing you can say about the animation in “Pinocchio”, it’s that it has plenty of character. “Pinocchio” was produced during the golden age of western animation, a time when much of a character’s personality was portrayed non-verbally through the animation, with longing stares, thoughtful, precise movements and sharp double-takes, requiring a lot of talent on the animators’ part (in fact, not long after this movie, Disney would try their hand at an experimental film where the animation does most of the work telling the story, called “Bambi“).

There are times when the film catches you off-guard with the sheer craftsmanship and ingenuity of the storyboarding and later the direction, like the detailed pan-ins of Pinocchio’s luscious, bustling village, Jiminy Cricket’s energetic POV shots, all the designs for the dozens of unfinished projects inside Gepetto’s workshop, and Monstro’s entire, massive girth crashing and barreling across the screen in a murderous rage – almost like a fiery storm. When it comes to the character designs for the humans, Disney has improved from their first primitive attempt in “Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs” and their designs look much more complex and natural this time around, though there are still a few cases here and there that wander into Uncanny Valley territory, like human Pinocchio at the end (who ironically looks stranger than puppet Pinocchio).

When it comes to the soundtrack, “Pinocchio” is one of those Disney works where the songs and the score blend together well, to the point where the songs feel more like an extension of the score than an interlude. I’m especially fond of how the score in the first act keeps returning to the melody of Gepetto’s lullaby, “Little Wooden Head” (along with how that moniker / term of endearment is later juxtaposed with Stromboli’s sneering taunt at the puppet, contrasting unconditional kindness with cruelty). The score by Leigh Harline and Paul J. Smith is actually fairly understated for a Disney film. It ambles along amiably for the most part, and grows steadily grows darker with the tone of the film, but for the most part it rests in the background, letting the dialogue and the atmosphere take center stage.

I appreciate how several of the songs involve characters scatting or improvising, like the old school performances “Give A Little Whistle” and “Hi Diddly Di (An Actor’s Life For Me)”. “I Got No Strings” is the most fun song of the lot, for how crazy and unpredictable it gets as Pinocchio performs alongside several other non-anthropomorphic puppets. The most famous song of the bunch is of course Disney’s tranquil anthem, “When You Wish Upon A Star”, which I honestly never knew was performed by Jiminy Cricket himself before discovering this movie. Lastly, I want to commend the foley work done in this movie, which I don’t usually draw attention to, for arranging such a diverse and authentic cacophony of sounds for Gepetto’s workshop at the start.

So all in all, “Pinocchio” is a surprisingly early magnum opus from Walt Disney Animation Studios and a great morality tale. As I said, the quality starts to wane a bit in the last twenty minutes with an ending that doesn’t make much sense, but it’s easily one of the strongest films produced by the studio during their golden and silver age, and a tour-de-force of quality animation.

Rating: 10/10.

Side-Notes:

* There is a surprisingly large amount of butt jokes in this family film from 1940 (Stromboli could teach Ursula a few things about “body language”), and this honestly made me smile. Some things never change.

* ‘My pets, you don’t like the name I picked for Pinocchio? Well, screw both of you, I’m keeping it’.

* “Oh, Figaro. I left the window open” Why are you so lazy, Gepetto? Close it yourself, bro.

* “QUIET!!!”

* As I live and breathe, a real fairy. Mmm-hmm!“.

* “Take the straight and narrow path and if you start to slide give a little whistle! Yoo-hoo! give a little whistle! Woo-hoo! I will always let your conscience be your guide!” “And always let your conscience be your guide! Wauugh!” “Look out, Pinoke!” Twenty minutes in and Pinocchio is already dead.

* “I’m dreaming in my sleep! Wake me up! Wake me up!” Alright.

* If Cleo gets lung cancer, she knows who to blame.

* I sometimes wish we could have seen more of the culture of Pinocchio’s little Italian village. What bit we do see looks pretty neat.

* “Go ahead! Make a fool of yourself! Maybe then you’ll listen to your conscience!” Jiminy Cricket feeling salty.

* Stromboli actually freaking screeches and reeeees when Pinocchio face-plants. Oh my god.

* “I guess he doesn’t need me. What does an actor want with a conscience anyway?” Dat burn.

* “Buck up, son. It could be worse. Be cheerful, like me!“.

* It’s funny how Pinocchio’s nose growing is considered a signature part of this story, when it really only happens once and is never mentioned again.

* “Goodbye Mr. Stromboli!” Pinocchio, no!

* Why do I feel like Pinocchio is always going to have a distaste for actors from now on?

* “I takes ’em to Pleasure Island” “Pleasure Island… Pleasure Island?! But the law! Suppose they-?!” “No, no. There is no risk! They never come back…. As BOYS!!!”

* A rather disturbing background detail (that it took me a while to catch) is Gideon being prepared to clobber Pinocchio with his mallet if Honest John doesn’t win him over his lies. On that note, I’m really glad the two cart him off and practically kidnap him (not like that), because if Pinocchio had willingly gone with them after they had already set him up with Stromboli before, he’d have gone from being a naive puppet to a really thick one.

* Lampwick gives zero fucks about Honest John, Pinocchio.

* Children get labeled jackasses several times in this movie. Add that to the growing list of things Disney could get away in the past that they never could now.

* I felt compelled to share these because I think they’re cute. Lampwick was only a part of this film for fifteen minutes, but like Figaro, the miscreant left quite an impression and I found myself almost missing him for the remaining twenty.

* So Pinocchio and Jiminy are going to at least try to do something about Pleasure Island after the film, right? Because now that they know the secret of what goes on there – child trafficking – it would be pretty messed up if they just kept that to themselves forever.

* “Father! Wait, he ain’t my father. Mr. Gepetto!”

* So can we talk about these parallels? Because I kind of want to talk about these parallels.

* Gepetto hugs that fish and then tosses it to the side. What a master of mixed signals.

* When Pinocchio tries to outswim Monstro and leaps out of the sea, he gets so much air. That puppet was trying his best to get away. Likewise, Pinocchio wastes absolutely no time thinking up an escape plan and putting it into action (he learned about fire in Act I and his pal Lampwick taught him how to wreck some shit in Act II), since he has no intention of staying inside a whale’s stomach for longer than five minutes. Good lad.

* “Father, why are you crying?” “Because you’re dead, Pinocchio” “No, I’m not” “Yes you are, now lie down”.

Further Reading:

- Nostalgia Critic; The Animation Commendation I and II; AnimatedKid; Silver Petticoat; Author Quest; Jess’s Somewhat Grown-Up Type Blog; All The Disney Movies; Disney In Your Day; Tor; Jaysen Headley Writes; The Disney Odyssey; Disneyfied Or Disney Tried?; Roger Erbert; This Is Random, But; A Year With Walt; A Year Of A Million Dreams; Blackbird’s Nest; Fernby Films; CokieBlum; Milmon Movies; Drew Martin Writes; Movie Feast; Doctor Film; Mr. Movie; Bibliophonic; Predictability Of Stupidity; Diamond In Rough Coal; NixPix; Eddie On Film; Kniggit; Hak’s Reviews; B Plus Movie Blog; Ten Stars Or Less; Film Music Central I, II and III; Standing On My Neck; Reviews Of Films; The Mouse For Less; Geeks Of Doom; Mighty Mike’s Raging Reviews; A Nerd Goes To The Movies; 1001: A Film Odyssey; Filmnomenon.

Fanfiction:

- Wish Carefully by Shelly Lane.

- Red Wood by MagicKoopa981.

- The Puppet by Sichrix.

- Pinocchio May Need Glasses by Hokuto Uchia.

- Questioning The Coachman by RustyRaccoon.

- A New Me by LuckyDuck932.

- Donkey Tails by LuckyDuck932.

- On The Willows by LuckyDuck932.

- Carton In My Pocket by LM Simpson.

- And Son by LuckyDuck932.

- Ti Amo by LuckyDuck932.

Thanks for the links!

LikeLike

I was glad to include them. I’ve always found your forgotten Disney characters series to be pretty interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I’ve recently started doing them for the DreamWorks Animation films now.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lady and the Tramp (1955) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: The Lion King (1994) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1996) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: Dumbo (1941) Review | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: Bambi (1942) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs (1937) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: Peter Pan (1953) | The Cool Kat's Reviews

Pingback: Cinderella (1950) Review | The Cool Kat's Reviews

my favorite disney movie, i just love foulfellow and gideon (my all time favorite disney characters) with the blue fairy, figaro and cleo too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

fun fact: foxes and cats has been my favorite animals for years, maybe because of this film (im not quiet sure?) because i love alot more animated foxes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s cool that “Pinocchio” influenced you like that. 🙂

LikeLike

well my other favorite animated foxes are fauntleroy fox from the columbia pictures cartoons and the one from baby huey show, if you haven’t seen these cartoons. check them out they are really funny and true forgotten classics that no one is talking about (which makes me sad because im a girl to obscure stuffs)

LikeLike